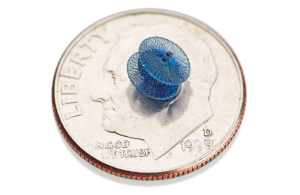

The Amplatzer Piccolo occluder from Abbott is one of the first medical devices that health providers can implant in premature babies weighing as little as 2 lb to treat patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in a minimally invasive way.

PDA is an opening between two blood vessels leading from the heart. It is one of the most common congenital heart defects in premature babies and accounts for up to 10% of all congenital heart diseases.

Approved by FDA in early 2019, Piccolo is a self-expanding, wire mesh, catheter-deployed device inserted through a small incision in the leg and guided through vessels to the heart, according to Abbott. The Abbott Park, Ill.–based medtech giant designed Piccolo to allow a physician to insert it through the aortic or pulmonary artery with the ability to retrieve and redeploy the device for optimal placement.

Because of the device’s small profile and its small market, the engineering behind the deploying catheter and device’s material can significantly impact its efficiency.

“The design of the catheter is an interplay of multiple factors,” Santosh Prabhu, head of R&D in Abbott’s structural heart business, told Medical Design and Outsourcing. “You need to pick the right materials for designing the catheter, construct it the right way and put in the right steering mechanisms so you’re able to deliver it through a narrow, tortuous blood vessel. You need the right combination of the stiffness of the catheter mixed with the flexibility.”

“Pediatrics are the most difficult environments to work in because everything is on a small basis,” said Mike Dale, SVP of Abbott’s structural heart business. “There’s a lot of real estate to work with in adults, so you can imagine what it’s like working with premature babies that literally fit in your hand. Whatever catheter might work in us is simply a non-starter for babies.”

Supporting an underserved market

When asked about recent pediatric device innovations, Dr. Gwen Fischer quickly mentioned Abbott’s Amplatzer Piccolo occluder. Fischer is director of the Pediatric Device Innovation Consortium, as well as pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) director at the University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital.

Pediatricians need even more devices for children such as the Piccolo to hit the market, because innovations in adult medical devices have outpaced the pediatric market for years, according to Fischer. The small pediatric patient population is underserved, and pediatric device developers often face challenges with funding and engineering. The market’s small size can hinder innovation and suppress an investor’s bottom dollar.

Physicians and surgeons often have to use products that aren’t approved for use in children. Sometimes they use a liver stent made for adults as a heart valve in kids. They could also use a product that is technically sized for a child but may not have gone through lengthy and costly clinical trials.

“When you’re trying to build something for such a small population, you need to be able to test it in clinical trials, and there just aren’t as many patients available for those clinical trials as there are in adult trials,” Fischer said. “It can be very difficult and expensive to run those clinical trials to make sure the device you’re making is safe and effective.”

A pediatric heart valve could make $10 million to $50 million in sales depending on what the device is, Fischer said. But the adult heart valve market is between $100 million and $1 billion depending on the device. The funding for pediatric medical device development boils down to whether investors want twice their money or 10 times their money. However, with a smaller market comes fewer investors, according to Fisher.

“It’s harder to find investment funding for those projects because you know the return on investment is going to be much lower than it would for an adult product,” Fischer said. “It’s not because they don’t support pediatrics because a lot of [investors] are very supportive of pediatrics in other ways. Most of them are beholden to shareholders or people that contributed funds. It’s just sort of the way of the world.”

Dale at Abbott said: “All the patients you want to treat are a smaller population. So, it’s a very high investment for a very small target population.”

“It’s difficult to organize the capital resources to do work in the pediatric area because there’s a high failure rate with your attempts and the actual markets are relatively small,” Dale said.

Pediatric devices can be difficult to engineer because children pose a unique challenge: They’re still growing. Their immune systems are constantly changing, their inflammatory markers change over time and their ability to clot and coagulate changes as well.

“If you’re trying to build a heart valve for a kid when they’re three, it’s going to be a different size when they’re 13,” Fischer said. “Those things can often be a bit of a barrier when it comes to pediatric medical device development.”

The market, though, is not as bad for noninvasive devices for children, according to Fischer.

“Things that we consider to be … an FDA-cleared product, the barriers to those are less now because you don’t necessarily have to do a clinical trial. You just have to show that you’re making it safely. It’s easier to get out something like a pediatric toothbrush than a heart valve.”

Kickstarting a pediatric medical device renaissance

Even with the small market, Abbott proceeded with the Piccolo because there was so much potential to improve patients’ lives — the company’s mission, Dale said.

Abbott isn’t alone in building medical devices specifically for kids and pediatric diseases rather than miniaturizing an adult product for a child. For example, Fischer pointed out Preceptis Medical’s second-generation Hummingbird tympanostomy in-ear tube system that is designed for in-office pediatric tube procedures without the need for anesthesia.

The FDA has done a lot of work to make it easier for companies to enter the medical device space. It has created a nationwide funding program and a consortium program that sponsors several pediatric medical device consortiums across the U.S. and funds pediatric medical device contracts. The FDA also connects industry professionals and people who know how to commercialize a device to help inventors bring their own devices to market. The agency states on its website that it is increasing the number of medical devices with labeling for pediatric patients by incorporating more known information about device effects in other patients to support more pediatric indications.

“I think we’re headed into a pediatric medical device renaissance of sorts,” Fischer said. “A lot of the low-hanging fruit has been picked when it comes to cardiac and other neurological areas. I think companies are looking for opportunities that are profitable, and there is a lot of profitable opportunities in pediatrics. It may not be 100 times your investment, but you’re going to have a return on investment.”