Studying mice, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis discovered that urinary tract infections (UTIs) can arise after sterile catheter tube insertion into the urinary tract. This can occur even without detectable bacteria in the bladder beforehand.

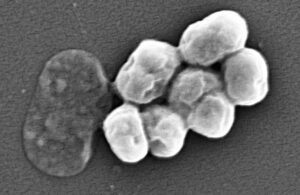

In mice, catheter insertion activated dormant Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii)bacteria hidden in bladder cells. It triggered the bacteria to emerge, multiply and cause UTIs, according to the researchers. They published their findings in Science Translational Medicine on Jan. 11. The findings suggest that screening patients for hidden reservoirs of bacteria could supplement infection control efforts.

“You could sterilize the whole hospital, and you would still have new strains of A. baumannii popping up,” said co-senior author Mario Feldman, a professor of molecular microbiology. “Cleaning is just not enough, and nobody really knows why. This study shows that patients may be unwittingly carrying the bacteria into the hospital themselves, and that has implications for infection control. If someone has a planned surgery and is going to be catheterized, we could try to determine whether the patient is carrying the bacteria and cure that person of it before the surgery. Ideally, that would reduce the chances of developing one of these life-threatening infections.”

More on the bacteria building up in catheters

A. baumannii can cause cases of UTIs in people with urinary catheters and pneumonia in people on ventilators. It can also lead to bloodstream infections in people with central-line catheters into their veins. Researchers say the bacteria are “notoriously resistant” to a wide range of antibiotics. This makes such infections challenging to treat with a real possibility of turning deadly.

Feldman teamed up with co-senior author Scott J. Hultgren, the Helen L. Stoever Professor of Molecular Microbiology and an expert on UTIs. Together, they investigated why so many A. baumannii UTIs develop after people receive catheters. Co-first authors Jennie Hazen (a graduate student) and Gisela Di Venanzio (an instructor in molecular microbiology) investigated, too.

The team used mice with weakened immune systems. Like people, healthy mice can fight off the bacteria, the researchers said. The mice had resolved infections with no bacteria detected in their urine for two months before receiving a catheter. Within 24 hours of catheter insertion, about half of the mice developed UTIs caused by the same strain of A. baumannii as the initial infection.

“The bacteria must have been there all along, hiding inside bladder cells until the catheter was introduced,” Hultgren said. “Catheterization induces inflammation, and inflammation causes the reservoir to activate, and the infection blooms.”

According to the researchers, about 2% of healthy people carry A. baumannii in their urine. They may never know they’re infected.

“This changes how we think about infection control,” said Feldman. “We can start considering how to check if patients already have Acinetobacter before they receive certain types of treatment; how we can get rid of it; and if other bacteria that cause deadly outbreaks in hospitals, such as Klebsiella, hide in the body in the same way. That’s what we’re working on figuring out now.”